Britain's railways were developed at a time of fanatical philosophical devotion to individualism and laissez-faire capitalism. Anyone could propose to build a railway anywhere: they got together investors, applied to Parliament for permission and, if it was granted, they were free to build it (using compulsory purchase if necessary).

Competition between railway companies was encouraged; monopolies were regarded as evil. (Indeed, in the earliest days railways were meant to be "public" utilities -- anyone could operate a train on payment of a toll to the railway company, in the same way that private toll roads operated. Fortunately the total insanity of this approach was quickly realised.)

For this reason, the British state took a passive, by-stander's view. Whereas in most other European countries the state took an active role -- by, for example, deciding where railway lines

should be built in the national interest, then by auctioning these routes off to developers -- there was none of that interventionist stuff in Britain. Instead, it was up to individuals to exert what influence they could (normally through either cannily devising a scheme to maximise the "accidental" return to the people in whose power it was to grant permission, or by outright bribery).

The net result of all this was a sort of insanity which put the needs of passengers a long way down the list of considerations. Through-running between different companies was not something much considered in the early days, and, in some cases, different gauges meant it was physically impossible to do so (there are, today, a number of ingenious solutions in place to overcome this problem, eg, in Spain and Russia).

A famous print from the "Illustrated London News" showing the mad scramble to change trains at Gloucester:

One of the other consequences of this hysterical competitiveness was the multiplication of railway stations in any town of a decent size. Glasgow, for example, had no fewer than four "main" central stations.

The ultimate expression of this was, of course, in London, which ended up with around a dozen mainline termini -- some, like Victoria (which opened in 1860), actually being

two quite separate stations built side-by-side: to access one from the other you had to leave, walk along the street, and then go back inside.

Victoria Station -- left-hand side:

...and right hand-side:

It was only in 1924 (after the two separate companies had been forcibly "grouped" into the Southern Railway) that a connection was finally opened up between the two.

Overseas, a more rational approach was usually adopted: in North America, for example, two or more railway companies would often co-operate on constructing a single "union" station to service a town or city, providing easier interchange for passengers and the opportunity (alas, usually not taken) to develop integrated transport facilities.

Incidentally, the name "Union Station" became so common that subsequently it was occasionally used for a station built and operated by just a single company.

The next photo is of Texarkana Union Station -- I chose this image because the only other occasion I have ever encountered that placename was in a pornographic short story by Lars Eighner in his magnificent collection of gay stories "BMOC". Or possibly it was in "American Prelude". I can't remember. Anyway, Texarkana:

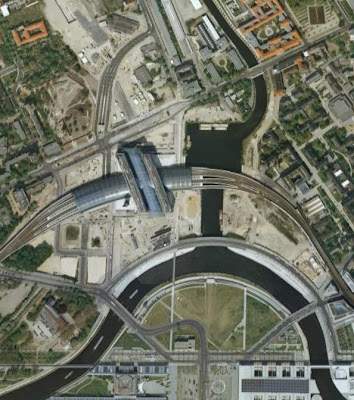

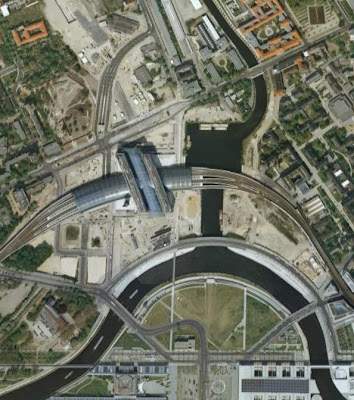

Shared stations happened even more frequently in the rest of Europe -- in Germany, for instance, most "hauptbahnhof" are centralised stations. Here's the glorious new central station in Berlin, where east-west routes cross north-south ones.

In Britain, it was often the case that a second company would gain permission to operate services to an existing station operated by another -- to take two examples, from Carlisle's Citadel station at one extreme, used by up to seven different companies (it ultimately restructured itself as a Joint Station, the British equivalent of a "Union Station"); to King's Lynn, a tiny station of the Great Eastern Railway which also had services operated by the miniscule Midland & Great Northern (M&GN) system.

From the ridiculous to the sublime: the rest of this post is a celebration of one of those European hauptbahnhof, in Dresden. Recently refurbished to designs by Norman Foster, this imposing building has been given a new lease of life.

The roof is a tent-like structure made from PVC, to a design by civil engineers Buro Happold.

Those repetitive arched forms are completely seductive.

The grandeur of the exterior of the building is a good match for that of the interior.

There's something insanely romantic about a train indicator board which begins with "Budapest":

Here's a view of the station in 1900, less than a decade after it opened:

To finish, a trio of images of a now-closed feature to one side of the station -- its very own cinema.

This was a not uncommon juxtaposition (people had time to kill while waiting for trains, so what better place to do it than in a cinema, watching a newsreel or a film?) -- London's Waterloo had a cinema as part of the station complex until relatively recently.

I am already fantasising about my own Cine York-style operation.

And if you don't know what that means, you need to go all the way back to

Apartment Zero...